Our Own Reckless Ways: Causes, Effects, & Solutions to Ocean Plastic Pollution

BY Kate LabodaAh how shameless – the way these mortals blame the gods.

From us alone they say come all their miseries,

but they themselves with their own reckless ways

compound their pains beyond their proper share.

Homer, The Odyssey, 1.37-40.

Squawking seagulls soar overhead, white and grey against the true-blue sky. You step out of your car and are immediately overwhelmed by the sharp smell and booming sound of waves. Running towards the tide line, you catch your breath as the icy water finally rushes over your feet. After a few moments of marveling at the vast horizon, you turn your gaze downward, searching for treasure within the sand around you. Thinking of your collection at home, you scour for a spiraled conch, purple oyster, ridged scallop, or even a rare pearly abalone. But today, you cannot seem to find any shells. Each time you reach down to examine the white or pink that catches your eye, you recoil. This beach, with its multicolored constellation of something, is not covered in shells, but in thousands of pieces of plastic. Suddenly, the clouds roll in and thunder strikes. You look around and the plastic transforms, morphing into a monstrous creature. It lurches forward, threatening to suffocate you. You think not only of your impending doom at the hands of this horribly synthetic creation but also of the countless species of fish and birds and mammals that swim through this landfill every day, mistaking garbage for food and getting entangled in the grasping strands of plastic.

This scene may seem plucked straight from a horror film, but beaches overflowing with trash are becoming more of a reality. For example, last winter after a series of storms, Seal Beach in California (see fig. 1) transformed into such a wasteland. Yet examples like Seal Beach have not spurred on widespread change. In fact, the plastic crisis has only gotten worse during the Covid-19 pandemic.

In an NPR interview, David Ford, founder of the environmental advocacy non-profit SoulBuffalo, argues that the coronavirus pandemic has led to an explosion of plastic pollution in the ocean. The main culprit? The 129 billion plastic face masks produced each month. In the words of Ford, this is “enough that you can cover the entire country of Switzerland with face masks at the end of this year, if trends continue […] there’s just no sign of that slowing down.” Many of the masks produced end up in the ocean, indicated by the 30% increase of oceanic pollution in the months since this pandemic began (Mosley and McMamahon).

Though there has been a recent increase in pollution, the plastic crisis is an ongoing topic of discussion and has been for decades. Despite the many efforts and innovations of scientists, organizations, and concerned citizens, plastic is still piling up everywhere. We hear stories of freak accidents and plastic contaminating on our beaches after unusual weather events, but the fact of the matter is, plastic accumulates on an everyday basis. In fact, a few weeks ago as I was walking the beach at Montauk State Park, I came across a plastic water bottle trapped inside a crabbing cage (see fig. 2). It reminded me of some kind of contemporary artwork–Waste Ensnared, plastic and metal, 2021–except this was real. We no longer need to turn to hypotheticals or carefully designed scenes to show there is a problem. We simply have to open our eyes and take stock of where our own reckless ways have led us.

With pollution levels increasing due to the pandemic, now more than ever, plastic increasingly dominates our lives and ends up in our oceans at alarming rates where it destroys wildlife and negatively impacts humans. In order to stem this issue, we must commit to personal changes to abandon single-use plastics and invest in sustainable alternatives.

Before we can discuss the negative impacts of plastic pollution, we must first understand how plastic use originated and how this waste ends up in our oceans. When you think of plastic, maybe a disposable water bottle or a flimsy take-out bag comes to mind. However, the first plastic was created to replicate billiard, or pool, balls originally made of ivory from elephant tusks (“A Brief History of Plastic”). The rapid decline of elephant populations in the mid 1800s due to overhunting forced the world to seek an alternative.

Fueled by the monetary prize for finding such an alternative, in 1863 John Wesley Hyatt created celluloid. This first plastic compound was made from cellulose, the structural carbohydrate found in plant cell walls. Unfortunately, for Hyatt, celluloid was not the right fit for billiard balls–it was not hard enough and had the nasty tendency of spontaneously combusting. Not to be discouraged, Hyatt discovered that celluloid could be dyed to mimic more expensive items such as pearl, coral, or tortoiseshell (“A Brief History of Plastic”). Costly items reserved for wealthy consumers were now made cheap with the advent of plastic dupes. As an article from the Science History Institute states, “advertisements praised celluloid as the savior of the elephant and tortoise” (“History and Future of Plastics”). Not only were cheaper copies of luxury items hitting the market, but they also came at no cost to the animal populations previously relied upon for these goods. Hence, the plastic revolution began.

The next major step in this revolution occurred in 1907 with the invention of Bakelite by Leo Baekeland. This was the first synthetic plastic, meaning it included no natural substances. Coined “The Material of a Thousand Uses,” Bakelite was less expensive, easier to mold, and would not lose its shape when heated (American Chemical Society).

The plastic revolution really took off, however, with the arrival of World War II. According to the Science History Institute, “during World War II plastic production in the United States increased by 300%” (“History and Future of Plastics”). The American military used plastic for everything: nylon was used for parachutes, ropes, and uniforms, while plexiglass made up cockpit windows (“History and Future of Plastics”). When the war ended and the curtain fell on the need for parachutes and helmets, these plastic production plants began creating items for the average consumer, such as shoes, toys, clothing, and food packaging. Plastic was suddenly everywhere. It truly was the “plastic century” (A Brief History of Plastic”).

As the use of plastic exploded around the globe, it was only a matter of time before it contaminated the oceans. But how does plastic get there? According to Mimi Ausland, activist and founder of Free the Ocean, two-thirds of plastic in the ocean comes from land-based sources (Unwasted Podcast). Plastic bags catch a breeze and escape from a landfill, granola bar wrappers are dropped on a trail and swept into rivers, and microbeads from face wash or toothpaste tumble down the sewer system. In short, all roads lead to the ocean.

While a majority of plastic pollution found in the ocean originates on land, the other one-third consists of waste from shipping barges and container ships. On November 30th, 2020, such a container ship, the ONE Apus, encountered a brutal storm on its voyage from Yantian, China to Long Beach, California. The massive waves from this storm caused many shipping containers to be lost overboard. In an initial investigation, it was found that 1,816 twenty-foot units crashed into the roiling waves (Link-Wills). Now to put this number in context, the average total loss of containers from these ships is about 1,800 each year (Ebbesmeyer). In a single incident, we lost the same number of units as is typically reported for a whole year. And of those lost, the contents of only sixty-four have been released. These contained “dangerous goods”: fifty-four held fireworks, eight contained batteries, and two were filled with liquid ethanol (Link-Wills).

In looking at a photograph of the ONE Apus in harbor (see fig. 3), even though the containers pictured in the photograph were not lost to sea, you can still imagine the devastation that occurred. Kim Link-Wills, senior editor of American Shipper and award-winning journalist, describes this image as “towers of containers [leaning] like a forest of felled trees. Other boxes hang precariously, poised it seems to soon drop into the sea” (Link-Wills). This image makes me wonder: was this incident that caused one of the biggest container losses in recent history just a fluke? Why don’t we know the contents of the majority of these containers? If a tree falls in a forest and no one hears it, did it even make a sound? Similarly, if thousands of containers fall into the ocean and no one reports its contents, did any damage occur? I think, yes. Since this waste is lost to the ocean, where it can have devastating impacts on wildlife and humans, it seems that we should know exactly what we are being exposed to.

In an effort to answer the questions posed above, I interviewed celebrated flotsamologist (one who studies flotsam, or overturned ship wreckage that circulates in the ocean), Dr. Curtis Ebbesmeyer, an oceanographer who has spent the last thirty years studying these incidents and tracking the abandoned contents of container ship wreckages. In fact, as an expert in the field, he was one of the first to shine a light on this mysterious issue. He was there in 1990 when five 40-foot containers fell overboard containing 80,000 Nike shoes; again in 1993 when containers holding 29,000 turtle, duck, beaver, and frog tub toys tumbled into the ocean; and again in 1997 when, off the coast of England, 5 million Lego pieces from (ironically enough) marine science kits were lost to sea (Ebbesmeyer). Clearly, the ONE Apus incident is not a fluke. When I asked what these shipping companies do when accidents like this happen, Dr. Ebbesmeyer clucked disapprovingly through the phone. He told me there is no requirement to clean up these spills or for the companies to even disclose what is in them (hence the lack of information from ONE Apus). Dr. Ebbesmeyer described this cover-up as “a dirty secret hidden in plain view” or “a dark corner full of black widows” (Ebbesmeyer). In order to save face, no information is given to the public, yet trash still accumulates in our waters.

Plastic particles may tumble off a ship in a container or fall from someone’s hand on the beach; however, once in the ocean the little plastic travelers get swept off into the ocean currents. These currents are caused by the heating and cooling of air on Earth’s surface. Air warmed by the sun rises, where it subsequently cools and falls back down. This cycle creates cells with high pressure pockets in the middle, and water is drawn there. The circulation of these currents forms gyres, whirlpools that turn endlessly, capturing “whatever we humans choose to throw into the sea or fail to keep out of it” (Ebbesmeyer and Scigliano 189). Plastic accumulates into what is known as “garbage patches,” a term coined by Curtis Ebbesmeyer. There are five main garbage patches (see fig. 4) spanning the world’s oceans. The largest patch, the Great Pacific Garbage Patch (GPGP), is estimated to be about twice the size of Texas.

If this largest patch is twice as large as the biggest continental state, how much plastic is really in the ocean? The specific amount is not known. Plastic is continually being added and subtracted (though the former occurs at a much higher rate) and some plastic is suspended in the water column or sinks, making it impossible to count the exact number of particles. However, according to the Ocean Conservancy, a nonprofit dedicated to the protection of our oceans, 8 million tons of trash enter our seas each year (Black).

On a trip to “Junk Beach” on the Southern coast of Hawaii where currents tend to abandon plastic on the shore, Ebbesmeyer remarks upon the constellation of multicolored plastic chips tumbling in the waves, saying, “I could not help thinking of a bizarre party, or parade; the sea was showering confetti on us, saluting the world we’d made by throwing bits of it back at us” (201). Not only does the ocean remind us of our plastic world through trash-covered beaches, but through its effects on the animal and human populations. Why is plastic pollution so detrimental? The answer to this question stems from the fact that plastic is permanent. Marine debris such as seaweed or drift logs eventually decompose, but plastic never disappears. Though larger pieces eventually break down into microplastics (0.05 to 0.5 cm in diameter), plastic can never truly vanish. Pieces may get smaller and smaller, but that only creates more and more particles. Plastic is infinite, invincible, and injuring.

Perhaps the most obvious detriment of oceanic plastic is its negative effect on marine life. And one of the most striking examples is the starvation of migratory seabirds. Take, for example, the albatross. These massive birds with wing spans of 6-10 feet spend most of their time gliding above the waves. In fact, some species of albatross travel five hundred miles a day and can even spend up to six years without touching land (Warne). Now, imagine yourself in this bird’s shoes (or wings). You fly across the endless, gray-blue ocean, when suddenly, a bright flash of silver catches your eye. There is no time to observe or calculate. A flash means food, so you dive and snatch up your shiny prey. Except, this is not a tasty mackerel. It is a discarded candy wrapper. The trouble is, with the presence of something in your stomach, you feel full even though this fish imposter will not lend you any nutrients. Birds that eat plastic have the sensation of fullness, but in reality, they have eaten nothing and die of starvation. An image of an albatross’s carcass filled with trash (see fig. 5) resembles a messed-up I-Spy: Who can find the lighter? Who can find the bottlecap?

When I was in sixth grade, I studied these birds and used a similar picture as inspiration for my final project’s diorama. I sifted through my own trash, picked out a few choice pieces, and glued them to a poster board. The glue-stick cap, fruit snacks wrapper, and other plastic objects were encased with a white, chalk outline of the albatross, similar to that of a murder victim’s body at a crime scene. I based my trashy display off a crime scene because that is what this is. Our waste kills these birds, a crime that all of us, even unknowingly, commit. In his recent National Wildlife Federation article “A Plague of Plastics,” award-winning journalist Barry Yeoman argues that an “inestimable” amount of sea birds die each year due to plastic consumption. So many birds die, we cannot even cite a reliable number!

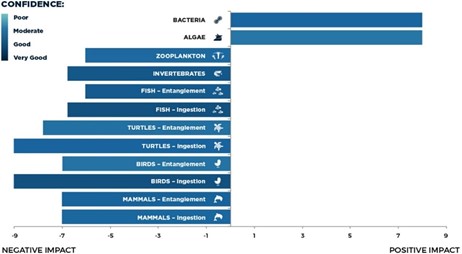

But plastic does not only affect sea birds. A graph on taken from a study conducted by Beaumont et al. and published in the Marine Pollution Bulletin (see fig. 6), indicates the effects of plastic on various marine animals. Depicted in the image, “a score of -9 means: lethal or sub-lethal effect which is global, highly irreversible, and occurring at a high frequency; a score of +9 means: positive effect in terms of diversity and/or abundance, which is global, highly irreversible, and occurring at a high frequency” (Beaumont).

As you can see, plastic is deadly to most animals. Larger animals such as whales or porpoises can get caught in neglected fishing nets or lines. Birds, sea turtles, and small mammals can be strangled by plastic rings. Like the albatross, turtles and other smaller animals mistakenly feast on plastic as well because, for example, jellyfish (a turtle’s natural diet) and plastic bags look very similar (see fig. 7). Due to plastic’s mimicry, it’s estimated that 52% of sea turtles have ingested plastic and for 22% of those cases, ingesting even one piece of plastic can be fatal (“What Do Sea Turtles Eat?”). And what about the thousands of jellyfish lookalikes that are the masks thrown away because of the pandemic? Maybe turtles think it has been an especially good year for jellyfish populations. I wonder if it will not be the opposite for the turtles themselves. Cruelly, the plastic that was once deemed a savior of animals and natural resources, is now starving, strangling, and entangling most of our marine organisms.

The only organisms that show a positive correlation to plastic in the graph published in the Marine Pollution Bulletin (see fig. 6) are algae and bacteria. This is due to the colonizing characteristics of bacteria and algae and the habitat that plastic provides (Beaumont). The nomadic tendency of algae and bacteria, while beneficial to the organism itself, can still cause catastrophic effects on the wider ecosystem. Usually, these tiny animals hitch a ride on seaweed or a piece of wood. These items will eventually decompose, and plankton, therefore, will remain in a fairly enclosed area. When they attach to plastic, however, which doesn’t decompose and can travel worldwide for decades, our little travelers have access to a much wider world. And as plankton travel farther, they can settle in unknown ecosystems, potentially introducing invasive species or dangerous toxins, all thanks to their handy chauffeurs.

Plastics do not just impact animals on the macro scale through entanglement, strangulation, starvation, and transportation. These organisms are impacted on the micro scale as well. Imagine every breath you take filled with toxic chemicals. Maybe there is a burning in your throat. Maybe you do not even realize the danger you are in until you are diagnosed with an advanced stage of cancer, or, more akin to what our oceanic friends experience, you just drop dead. When plastic particles break down, they release chemicals into the ocean, creating a deadly cocktail that marine animals are force-fed every day. One such chemical is PCB (polychlorinated biphenyl) which mimics the female hormone, estrogen. It binds to estradiol receptors like a villainously copied key to its unsuspecting lock, triggering lactation, development of genitalia, and estrus (female fertility). Without an outlet via reproduction, these “estrogen bursts” can lead to anemia, liver cancer, and neurological damage to those creatures who ingest it (Ebbesmeyer and Scigliano 213). Due to the harmful nature of PCBs, the substance was banned in the 1970s. However, if you recall, plastics do not decompose. This means that decades-old plastic still circulates through the water, leaching out its toxins to this day.

The danger of these toxins also increases at higher levels of the food chain through a process called bioaccumulation (“The Great Pacific Garbage Patch”). Recall the phrase “you are what you eat” from elementary school health classes. This adage also applies to the marine food webs. When a whale eats a seal, which ate some fish, which ate some plankton, which ingested plastic, the whale inherits all of the accumulated toxins from the meals of his meal. And humans are not immune. We are at the top of the food chain. When we eat a juicy salmon, for example, that has been contaminated with PCBs, those toxins accumulate in our own bodies, increasing our risk of fertility issues, developmental deformities in future generations, and cancer.

Plastic pollution does not only impact humans through poisonous chemicals, however. According to the study conducted by Beaumont et al., there are three ways in which marine plastic negatively impacts the wellbeing of humans:

- Food access

- “Heritage” (beneficial connection to marine organisms)

- Social/recreational experiences

In explanation of this first point, seafood makes up about 20% of the diet for 1.4 billion people on this Earth (Beaumont). Due to a decline in fish populations resulting from plastic pollution, our waste robs certain communities of their primary protein source. For example, an overwhelming presence of plastic waste plagues the fishing village of Muncar, Indonesia. According to Muncar’s mayor, Lukman Hakim, quoted in John Vidal’s HuffPost article, “The fish catch is declining because the plastic sits on the feeding ground of the fish. It interferes with the propellers of the fishing boats.” In a town home to sixty fish farms and 108 miles of coastline, this pollution may be catastrophic (Vidal).

To support the second point, this study references “charismatic” ocean animals such as whales or dolphins that charm and excite us, improving our state of mind. When these large marine mammals turn up beached due to entanglement in discarded fishing lines, for example, this can hurt our wellbeing. It pains us to see these gentle giants suffer. According to Beaumont et al, “humans experience wellbeing in the knowledge that marine animals are there and will remain for future generations, even if they never directly experience them” (Beaumont et al). Some of you may be privileged enough to have experienced these “charismatic” creatures firsthand. Perhaps you have witnessed a leatherback sea turtle lazily gliding through the water, the sunlight bouncing off his patchwork green shell. Maybe you’ve “ooh-ed” and “aah-ed” with fellow aquarium visitors as the sea otters in front of you somersault over and over scratching each part of their fur-laden bodies. I, similarly, had one such experience with these “charismatic” animals. Sitting on a beach in Mexico, knees pulled in tight with anticipation, I could just make out the gray, hazy outlines of humpback whales leaping out of the ocean. I was not even close enough to see the resounding crash of waves as they walloped back into the water, but I was content. Even though they were so far away, I was relieved and thrilled to know that they were there at all.

The third point that this study mentions is how plastic pollution negatively impacts our social and recreational activities. Imagine you are planning a beach day. You have packed the sunscreen, beach towels, and water bottles (reusable, of course). As you near the beach, you roll down the window and are hit with the fresh and biting smell of the salty water. But when you get out, all you are met with is trash as far as the eye can see. According to the Beaumont et al study, trash is one of the main reasons why people do not go to the beach. And when people skip out on sunbathing or surfing, they also miss out on the benefits of being outdoors with friends and family. We miss an opportunity for human connection, not to mention the boost in positive feelings and reduction in stress that a nice, sunny day in nature is proven to give you. In fact, ecotherapy has been a very successful tool in limiting the stress and improving the health of addicts, veterans with PTSD, and patients recovering from abuse.

One such example is a wilderness therapy program, Rivers of Recovery (ROR), which takes veterans on fishing trips where they spend time in the wilderness and learn relaxation techniques. In a study conducted by researchers from the University of Southern Maine, the University of Utah, and the Salt Lake City Veterans Administration, sixty-seven veterans reported that “perceptual stress had gone down 19 percent; physical symptoms of stress decreased by 28 percent; sleep quality improved 11 percent; depression lessened 44 percent and anxiety 31 percent” after a 4-week ROR wilderness trip (Nichols). This data is all based on self-identified results. Of course, the best way to prove the validity of the stress-reducing power of nature is to try it for yourself. Personally, I found that walks in the New York Botanical Gardens helped ease the anxiety of writing this essay.

Being in nature–and especially by water–is proven to reduce stress and anxiety, but sometimes we choose not to go to beaches because they are clogged with trash. What can we do about it? Some organizations aim to help curb this issue by physically removing plastic from the oceans. The Ocean Cleanup, for example, is a Dutch nonprofit organization that seeks to reduce plastic in the oceans by 90% come 2040. Current models suggest that they can reduce the amount of plastic by 50% in just five years. Their technology (see fig. 8) involves a horseshoe-shaped catch system that moves in the same direction as the ocean currents to conserve energy and limit damage (“Marine Litter”). If this works, trash would accumulate inside the horseshoe, ripe for removal.

Another organization aimed at trash removal is the nonprofit Free the Ocean in partnership with Sustainable Coastlines, Hawaii. Every day you can visit Free the Ocean’s website and answer a trivia question to remove a piece of plastic from the ocean (in fact, let us all click on this URL: https://www.freetheocean.com/ right now. It is fast, easy, and you can play a part in removing plastic one piece at a time!). Due to ad revenue, each answer removes one piece of plastic from the ocean by funding the removal work of Sustainable Coastlines, Hawaii (“Eliminating Ocean Plastic”). As of writing this essay, the site has removed just over 14 million pieces of plastic (“How it Works”). This number is impressive, until you realize that about 8 million pieces of plastic get dumped into the ocean each day (“Eliminating Ocean Plastic”). So, since the beginning of this program in August 2020, we have removed one and three quarters days’ worth of trash. It is like trying to remove water from a river by the cupful when a waterfall stands behind you, gushing hundreds of liters into the river each second.

By simply removing plastic, we will never fix the problem. We must stop plastic pollution at its source, damming the river upstream to stop the flow of the waterfall. We can do this through personal life changes, banning single-use plastics, and investing in sustainable technology. It is a tale as old as time, but reduce, reuse, recycle. Channel your inner VSCO girl and drink through that metal straw with pride! Following is a short list of simple, personal life changes we can all take to reduce plastic pollution:

- invest in reusable water bottles instead of single-use plastic bottles

- purchase reusable Tupperware instead of plastic bags

- carry your own set of utensils rather than throwing away disposable sets

- buy bars of soap to limit the disposal of plastic containers

- wear washable cloth face masks rather than single-use plastic ones

Change must also come at a federal level by implementing laws that reduce single-use plastics and promote sustainability. Many countries have already started this process. As of 2018, 127 countries have implemented laws banning plastic bags. Eight countries, including the United States, have outlawed microbeads in soaps and toothpastes, and in 2019 the EU banned all single-use cutlery (Yeoman). Now, we look to sustainable alternatives. Many restaurants and fast-food chains, for example, have started carrying compostable utensils made of potato starch. In Surabaya, Indonesia, individuals can pay for bus rides with collected plastic bottles, a measure that helps remove up to three tons of plastic waste a day (Vidal).

Another wide scale attempt to reduce plastic pollution is ReSource, an initiative funded by the World Wildlife Fund. Founded in 2019, ReSource encourages big companies (originating with McDonalds, Starbucks, Keurig Dr. Pepper, Proctor & Gamble, and the Coca-Cola Company) to analyze how plastic is used and track plastic pollution (helping to fill the gaps left by container ship spillages described earlier in this essay). The goal of ReSource is to keep 50 million metric tons of plastic waste out of our seas by 2030 (ReSource Plastic, “Transparent 2020”). To do this, they seek to eliminate single-use plastic, increase the amount of recycled plastic used in production, and “double global recycling rates” (ReSource Plastic, “Key Resources”). In other words, they strive for a cyclical economy in which we only use the plastic we need and recycle rather than dispose. This contrasts with the wasteful and pervading linear economy we currently experience where most of the virgin plastic is produced, used, and immediately thrown away. Fifty million tons in ten years seems ambitious, but holding big companies accountable for their plastic usage is one of the first steps to reaching this goal.

Despite this overwhelming problem we face, there is still hope. In the words of Yeoman, “If we immediately [stem] the flow of debris, nearly all the plastic in the ocean’s surface layer – where it harms so much wildlife – would disappear within three years” (Yeoman). It is naïve to think that we can immediately stem this flow, for plastic is so dominant in our lives. Yet it is our own reckless ways that have led us to this crisis, so we are the only ones who can alter our synthetic fate.

These changes will take time, but the sacrifices they might require are insignificant when compared to the possible benefits. With the necessary reduction of plastic, our rivers will run clean, turtles will be able to breathe again, and sea birds can dive down to catch their prey in confidence. We will not falter before buying salmon in the supermarket because PCB levels will have dropped, and we can plan bonfires on the beach surrounded not by trash, but by friends. Maybe it will take ten years, maybe a hundred, but one day someone will step out on the beach, shell collection pail at the ready. They will wiggle their toes, relishing in the cool, solid sand beneath them. As waves lap at their feet and they start walking the stretch of beach, they spot flashes of white and pink and purple. Shells, all of them. There is not a plastic monster in sight.

Works Cited

“A Brief History of Plastic.” YouTube, uploaded by TEDEducation, 10 Sept. 2020, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9GMbRG9CZJw.

American Chemical Society National Historic Chemical Landmarks. “Bakelite: The World’s First Synthetic Plastic.” http://www.acs.org/content/acs/en/education/whatischemistry/landmarks/bakelite.html.

Beaumont, Nicola J., et al. “Global Ecological, Social and Economic Impacts of Marine Plastic.” Marine Pollution Bulletin, Pergamon, 27 Mar. 2019, www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0025326X19302061.

Black, Madeline, and Nick Mallos. “Plastics in the Ocean.” Ocean Conservancy, 17 Dec. 2020, http://oceanconservancy.org/trash-free-seas/plastics-in-the-ocean/.

Ebbesmeyer, Curtis. Personal interview. 13 Dec. 2020.

Ebbesmeyer, Curtis C., and Eric Scigliano. Flotsametrics and the Floating World: How One Mans Obsession with Runaway Sneakers and Rubber Ducks Revolutionized Ocean Science. HarperCollins, 2009.

“The Great Pacific Garbage Patch.” The Ocean Cleanup, 11 Feb. 2020, http://theoceancleanup.com/great-pacific-garbage-patch/.

“History and Future of Plastics.” Science History Institute, 20 Nov. 2019, http://www.sciencehistory.org/the-history-and-future-of-plastics.

“How It Works.” Free The Ocean, http://www.freetheocean.com/how-it-works/.

Link-Wills, Kim. “Storm-Beaten ONE Apus Berths in Japan.” FreightWaves, 8 Dec. 2020, http://www.freightwaves.com/news/storm-beaten-one-apus-berths-in-japan.

“Marine Litter.” PlastEurope.com, 12 Dec. 2018, https://www.plasteurope.com/news/MARINE_LITTER_t241412/.

Mosley, Tonya, and Serena McMamahon. “COVID-19 Pandemic Has Led to More Ocean Plastic Pollution.” Here & Now, http://www.wbur.org/hereandnow/2020/10/12/plastic-pollution-coronavirus.

Nichols, Wallace J. Blue Mind: the Surprising Science That Shows How Being near, in, on, or under Water Can Make You Happier, Healthier, More Connected and Better at What You Do. Little, Brown Spark, 2015.

ReSource Plastic. “Key Resources.” World Wildlife Fund, http://resource-plastic.com/more.

ReSource Plastic. “Transparent 2020,” http://resource-plastic.com/pdf/Transparent2020.pdf.

Vidal, John. “How A Picturesque Fishing Town Became Smothered In Trash.” HuffPost, HuffPost, 29 May 2019, http://www.huffpost.com/entry/indonesia-plastic-waste-pollution-solutions_n_5cabc096e4b02e7a705c317c.

Unwasted Podcast. “Eliminating Ocean Plastic with Mimi Ausland.” 16 Nov. 2020. https://thewholecarrot.com/2020/11/mimi-ausland-ocean-plastic/.

Warne, Kennedy. “The Amazing Albatrosses.” Smithsonian.com, Smithsonian Institution, 1 Sept. 2007, http://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/the-amazing-albatrosses-162515529/.

“What Do Sea Turtles Eat? Unfortunately, Plastic Bags.” World Wildlife Fund, http://www.worldwildlife.org/stories/what-do-sea-turtles-eat-unfortunately-plastic-bags.

Yeoman, Barry. “A Plague of Plastics.” National Wildlife Federation, http://www.nwf.org/Home/Magazines/National-Wildlife/2019/June-July/Conservation/Ocean-Plastic.