The Evolution of the High Line

BY Kathryn ZeiglerNew York City experiences constant growth and change. Its places and destinations become altered with time and adapt to what is needed or wanted within society. These changes and alterations all make up a history. Knowledge of what stood before and how the present condition came to be are all important aspects of history that add value to a particular place. One place that deserves more appreciation because of its history is the High Line, located on Manhattan’s West Side. The 150-year evolution of the High Line is very unique. When it was destined to be demolished, citizen involvement kept it alive and its purpose completely changed. To fully appreciate the High Line, one must know how the space developed to be the flourishing park what we see today.

Weaving between buildings of Manhattan from Hudson Yards to Chelsea, the High Line is a 1.45-mile elevated public park and walkway (Friends of the High Line). With beautiful views of the Hudson River, the High Line is filled with blossoming gardens at every turn accompanied by benches to relax on, colorful abstract art, and food vendors that change with the season. Its paths contain unique views as well as an alternate route for foot transportation. Operated by a nonprofit organization called Friends of the High Line in partnership with New York City’s Department of Parks & Recreation, the park became an instant hit for tourists to visit and for West Siders to lounge when it opened in 2009 (Friends of the High Line). Its elevation above the streets of Manhattan gives it a unique feature compared to the other classic public parks. This elevation is a result of the history of the High Line that many people are unaware of. The pathway of the High Line has been preserved since the mid-1800s. Starting off as a street level railroad, turning into an elevated railroad, and then almost destined for demolition, the High Line contains over 150 years of history (Friends of the High Line). It experienced radical change to become the blossoming public park that it is now. These events leading to its success and current condition are unknown to many tourists who visit it or citizens who use it for their leisure walks. One hundred and fifty years of history lie in the same 1.45-mile path that over seven million people visit yearly (Ganser).

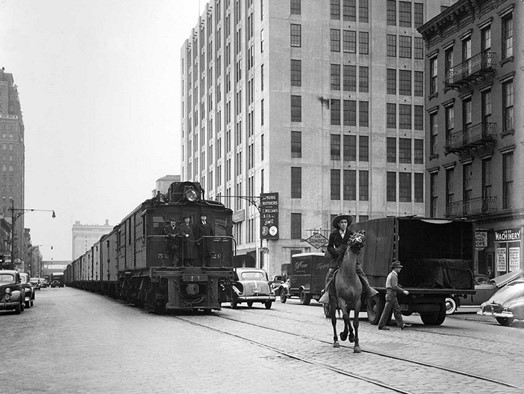

In the mid-1850s freight trains raced down the streets of New York City, serving as the most popular way to transport goods. Running only a few feet away from cars, pedestrians, and horses, freight trains became a major danger because there was no technology to warn people of their presence (Image 1). Over five hundred and forty people died on 10th Avenue from these trains by 1910. These numerous deaths made freight lines realize a change needed to be made regarding their path of transportation. In 1924, the idea was formulated to remove the tracks from ground level and elevate them for safety reasons. This elevated track commenced in 1934 and was called the West Side Elevated Line. This line was a narrow elevation containing two side-by-side tracks that ran directly in between buildings and factories. This close proximity to buildings created for more convenient deliveries of cargo (Image 2). The West Side Elevated Line traveled on the same path that the High Line stands today with an additional Southern section (Friends of the High Line).

Thirty years later, trucks became a more efficient and widely used way to transport cargo. This led to the decrease of use in the elevated railroad and eventually the closing of the Southern section in the late ‘60s (Friends of the High Line). Afterwards, it was demolished, leaving the pathway of elevated railroad that the High Line travels today. In the next twenty years, the popularity of trucks only expanded. This popularity led to the full decommission of the West Side Elevated Line. With no more running trains, the elevated structure was destined to be demolished.

In 1983, the first ideas were voiced to save the structure that the West Side Elevated Line once ran on and use it for something else. That same year, the National Trails System Act was passed, which benefited the initiative to salvage the elevated abandoned railroad because it called for the establishment of public trails in urban and rural settings to promote interaction with nature (“National Trails System Act Legislation”). Citizens of Manhattan used this to rebuke the demolition. They pleaded for the conversion of the remnants into a type of green space that was called for by the newly proposed legislation. Ultimately, the National Trails System Act manifested this idea and led to the opening of the High Line as a public park twenty-six years later.

Although this ruling sparked a possibility for change, the idea was not acted upon immediately. The abandoned elevated structure sat unused for seventeen more years. Crowded with overgrown weeds and a sense of lifelessness, its deteriorating looks became a constant complaint on the Lower West Side. Its supporters began to waver, and in 1999 Mayor Giuliani signed it to be demolished (Friends of the High Line). With this final demolition order came the most successful attempt to stop it. That same year, Joshua David and Robert Hammond created Friends of the High Line, the organization that is responsible for the park now. These two men saw beauty in the abandoned space and its flourishing garden of wild plants and weeds. This greenery in what had been dull and dead for many years inspired them to try and assist the renovation of the High Line into what it is now (Friends of the High Line).

In 2003, David and Hammond were not fully certain the area would be turned into a park, so they called on the help of the public. Friends of the High Line created an ideas competition that gathered 720 designs from people in thirty-six different countries. Some ideas were practical and led to the creation of its greenery, art, and benches. On the other hand, Jerina Wan Aikshan wrote about some unique ideas that included “a clear-bottomed pool and a grandstand rising off the trestle” (Wan Aikshan). This competition raised awareness about the renovation of the space and allowed more people to pay attention to its remodel. In addition, it allowed people to voice their opinions, thereby showing that the public truly had a say in what would happen to this historic space. Public influence in the High Line’s revival is one of its most admirable aspects and should be known by visitors.

In 2009 the first part of the High Line opened to the public through the work of Friends of the High Line (Friends of the High Line). The organization established a partnership with the New York City Department of Parks and Recreation, which maintains all of the city’s public parks. Friends of the High Line gained full stewardship of the walkway, gardens, and art that now make up the public park. The idea of creating a park stemmed from a combination of submissions in the ideas contest. In 2014 the entire thing was open to the public and looked the same as we see it today. The modern structured flooring and benches lined with neat landscaping are the products of years of change. While some of its original path has been demolished and changed to other things, the existing stretch of what is now the High Line is the same path that the freight trains ran on street level in 1850s. This preservation and history are seen through the parts of the railroad that are still on the High Line, covered in greenery on the side of the walking path (Image 3).

To have this path of travel preserved in a city that constantly experiences growth and change is something very special and needs to be recognized by all High Line visitors. The recognition of this history could be promoted by Friends of the High Line, with facts about the transformation and “before” photos scattered throughout the walkway on signs. With these signs in place, people will be educated about the park’s history while they are enjoying its current condition. Because visitors will see how the current space has changed and learn about what it was in years before, the signs will be the catalyst for recognizing its uniqueness and cultivating a new sense of appreciation. Instead of the High Line just being a place to walk, it will be thought of as a preserved space with over a hundred years of history that benefits the city by providing much-needed greenery and a break from fast-paced life with a place to relax.

In addition to what the space of the High Line once was, people need to be aware of how it became what it is now. Citizens fought for years to keep the structure intact and create the space that is present. From voicing ideas about what it could be converted to in 1980, to speaking out against demolition bills in 1999, the public is the reason the railroad structure was converted into the green space we see today. The effort that citizens put into maintaining the structure should inspire others. The High Line represents the power people have to make change in their own area: people who saw value in saving the elevated railroad acted to convert it into a beneficial place for the public. If citizens and tourists knew this when they visited the public park, it might encourage them to take the same action in their communities. It is a fabulous symbol for what citizen involvement can do by turning around a government decision to create a beautiful space that is used by millions. When seeing what the High Line has become because of public involvement, people should never doubt their power as a citizen.

Most people don’t know the history of this park, but I believe that its historical aspects and creation by the public should change the way people interact with it. It serves as a symbol of societal change, economic growth, resilience, and citizen impact. When one fully understands these symbols and how they came to be, it provides an entirely new outlook about the High Line. Knowledge of the historical background and what it represents should create a new level of appreciation. With this new level of appreciation, people will view it as more than just a park and understand why it is so special. Every time they encounter the High Line, they can understand the changes it has gone through to become what it is today. They can also be inspired by the passion and effort put in by everyday people to make it what it is. The High Line is not just a beautiful walkway but a pathway of history that deserves to be appreciated by everyone.

Works Cited

Ganser, Adam. “High Line Magazine: B1G DA+A and Parks.” The High Line, 16 July 2018, https://thehighline.org/blog/2017/01/18/high-line-magazine-b1g-daa-and-parks.

Friends of the High Line. “History.” The High Line, 2000-2020, https://thehighline.org/history.

“National Trails System Act Legislation.” National Parks Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, 4 Apr. 2019, https://nps.gov/subjects/nationaltrailssystem/national-trails-system-act-legislation.htm.

Scherer, Jenna. “The Ultimate Guide to the High Line in NYC.” Curbed NY, Curbed NY, 7 May 2019, https://ny.curbed.com/2019/5/7/18525802/high-line-new-york-park-guide-entrances-map.

Wan Aikshan, Jerina. “High Line Competition.” NYC StudioArch, Dec. 2013, https://cargocollective.com/Uofanycstudioarch/high-line-competition.