After 27: Kurt Cobain’s Legacy

BY Christopher Kerrane- Content Warning: This essay discusses self-harm, suicide, and the death of Fordham student Sydney Monfries.

From the late 1980s to early 1990s, grunge band Nirvana’s music served as the soundtrack of a generation and orchestrated the evolution of rock music and culture. The nature of lead singer and guitarist Kurt Cobain’s suicide at age twenty-seven often overshadows his remarkable achievements in one of the most influential and iconic musical acts of all time. In his short lifetime Cobain changed the landscape of rock music and deserves to be remembered for his innumerable contributions to pop culture, as opposed to the personal struggles he endured that were magnified by the media. Not only did Cobain bring grunge and punk rock into the mainstream, but he also promoted inclusivity in a historically chauvinistic genre, and inspired a generation of listeners as an anti-rock[1] rock star. Cobain’s music and enduring status in pop culture have survived to inspire the next wave of rock music, in whatever form it takes.

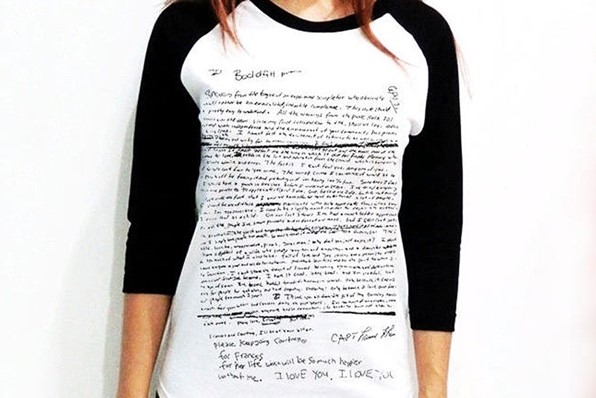

The legacy of Cobain’s professional accomplishments lives on, but is sometimes concealed by the memory of his tragic suicide. A 2015 Billboard article reported that several websites, including eBay and Etsy, were selling t-shirts with the words of Kurt Cobain’s infamous suicide note imprinted on the front (Figure 1). Condemning the production of the shirts as “the most tasteless memorial to the Nirvana frontman’s life,” Chris Payne argues that the commercialization of Cobain’s final sentiments to his wife and child was completely inappropriate (Payne). The production and sale of these shirts over twenty years after Cobain’s death illustrates the public fixation on his suicide, and how this fixation can detract from his life’s accomplishments. Beginning with the publication of this intimate letter shortly after Cobain’s death, the privacy of his final moments has been continuously violated since 1994.

Years after the suicide note’s original composition, manufacturers rehashing Cobain’s darkest words in order to make a profit underlines the extent of the public’s enduring obsession. Relentless preoccupation with Cobain’s death can also be noted in controversial documentaries, such as Kurt & Courtney (1998) and Soaked in Bleach (2015), which delve deeply into Cobain’s personal life and go as far as to suggest alternate theories of his cause of death, including that his wife Courtney Love murdered him. While conspiracy theories and biographic documentaries are not revolutionary, it is important to note that these fixate mostly, if not principally, on his personal struggles and suicide. The focus of these documentaries indicates that while Cobain is recognized for his professional successes, they are often overshadowed by his devastating death.

One of Cobain’s closest friends claims that the narrative of the bitter end of his life is not fully indicative of the person he was. Danny Goldberg, former co-manager of Nirvana, characterizes him as an empathetic, brave, and talented musician. Goldberg’s 2019 memoir Serving the Servant: Remembering Kurt Cobain gives insight into the individual behind the rock star. In an interview with Rolling Stone, Goldberg recalls how he felt when Cobain died: “I will never completely get over the sadness and anguish I felt at that moment” (Martoccio). The interview reveals a different side of Cobain’s interpersonal relationships and illustrates the impact he has had on future generations. For instance, Goldberg notes the influence Nirvana has had on popular culture: “There are people I see wearing Nirvana t-shirts that probably were not even alive when Cobain died. There’s something about the music that he wrote and sang that transcends generations. That’s a rare thing” (Martoccio). From the former manager’s point of view, Nirvana’s legacy has seen a musical rebirth with younger listeners as illustrated in Figure 2.

This reinvigorated legacy has allowed Nirvana’s music to be digested over twenty-five years later by a new generation, while still being appreciated by the generation that came of age during the height of Nirvana’s success. Goldberg recognizes the power of this legacy and uses his memoir to shine light on Cobain’s artistry above his tragic death. Instead of rehashing the unfortunate and untimely end of Cobain’s life, Goldberg emphasizes the positive qualities and strengths Cobain exhibited, such as his “unforgettable smile” and undeniable talent (Martocio). Largely due to his tragic death and highly publicized suicide note, people often forget this “unforgettable smile” Goldberg mentions, and the joy that Cobain brought to thousands. Goldberg’s memoir substantiates the claim that Cobain’s strength as an individual and musical brilliance as a boundary-breaking artist are often overlooked. The memoirist’s desire to shift the focus from Cobain’s suicide to his artistic integrity reveals the importance of not allowing a tragedy to eclipse one’s legacy.

Though long before the height of their popularity, the events of Cobain’s early life are often overlooked in their influence of his grunge identity in pop culture. His youth in Aberdeen, Washington was largely shaped by his parents’ divorce in 1976 and his subsequent delinquencies, such as substance use and vandalism. He did not finish high school, and instead moved to Olympia, Washington in 1987 with his newly formed band that selected the name Nirvana in 1988. Soon after, they were signed to a record label in Seattle and released their debut album Bleach. The style of music they embodied came to be known as “grunge” and slowly gained popularity in punk and metal scenes (Rubin). Reflecting on his major move to Olympia in a 1989 interview, Cobain expressed his pleasure with leaving home and his troubled youth behind. He recognized its effect on his music, noting, “I’ve written most of the material on this record out of Aberdeen… all of the material on this record was written in Olympia… the songs are getting poppier [sic] and poppier as I’m getting happier and happier” (Aubrey). In the public memory of Cobain, his blue-collar suburban roots are often underestimated. However, these roots serve as important background to how Cobain reached pop culture icon status by relating to thousands of fans with the shared angst of youth.

Cobain and Nirvana’s second studio album, Nevermind (see Figure 3), not only skyrocketed them to international fame, but reshaped the music landscape and continues to inspire musicians to this day. Critics and fans alike believe that this album stands out from others as it “accentuated Cobain’s melodic gifts” through his “pained, nihilistic lyrics” (Rubin). For example, the music video for “Smells Like Teen Spirit,” which became an MTV and radio sensation, depicts Nirvana performing to a group of apathetic teenagers in a school gymnasium, with the “disaffected youth” moshing at the apex of the chorus (Rubin). Adolescents around the country resonated with this message of rebellion and the rejection of social norms.

As the song and the album flew to the top of Billboard charts, the grunge sound of Nevermind was beginning to shape a generation’s identity. In reference to “Smells Like Teen Spirit,” a journalist and member of Generation X reflects on the emotional power of Cobain’s vocal style: “I didn’t know what he was saying, but I didn’t need the words to know what he was feeling, a mix of turbulent and conflicting emotions I too had felt but couldn’t always name” (Hamburger). Cobain often validated teenage angst and frustration by using music to make listeners feel less alone. A vital element of his legacy is the voice he gave to this group of young fans and the unity his music promoted.

Music journalists have hailed Nevermind’s persisting impact on the music industry. Recognizing Nevermind’s widespread influence, music journalist James Hall asserts, “Musically it [Nevermind] popularized a sound and a DIY aesthetic without which there’d arguably be no Arcade Fire or Radiohead, White Stripes or Wolf Alice” (Hall). Cobain and Nirvana introduced a new wave of rock music that would determine much of what was to come. In terms of culture, Nirvana simply “obliterated the distinction between underground and mainstream and marked a brutal end to the baby-boomer era” (Hall). With the popularization of grunge fashion and inclusive anthems like “Come as You Are,” Nirvana expounded adolescence of the early 1990s (Nirvana). Bringing such a distinct subculture into the mainstream, Nirvana forged an undeniable cultural identity that linked 1990s teenage life with the aesthetics and sound of the band. The cultural impact of Cobain’s music, along with the shaping of the rock genre for years to come, are indisputable aspects of his multi-faceted legacy.

Cobain’s influence can be found in various musicians, albums, and songs that rose to prominence long after Nirvana ended. One example is 1999’s “Adam’s Song” by Blink-182, with the lyrics “I took my time / I hurried up / The choice was mine I didn’t think enough” (Blink-182). These words echo a verse in the iconic single “Come as You Are,” which flows as “Take your time / Hurry up / The choice is yours / Don’t be late” (Nirvana). Blink-182, which dominated another rock-infused subgenre known as pop punk, represented a later generation that could still relate to the words that Cobain had written. Released over twenty years after “Smells Like Teen Spirit” became the national anthem of teenage emotion, the chorus of Jay-Z and Justin Timberlake’s “Holy Grail” is set to the tune of “Smells Like Teen Spirit” and goes as follows: “And we’re all just entertainers / And we’re stupid, and contagious / Know we all just entertainers” (Jay-Z, Justin Timberlake). Like Blink-182’s “Adam’s Song,” “Holy Grail” exhibits Cobain’s cross-genre and cross-generational influence as a songwriter and cultural icon.

Cobain’s trendsetting and positive influence extends beyond the music itself. As a public figure ahead of his time, Cobain advocated for LGBT+ rights and feminism, social justice topics that were considered taboo for popular rock stars to discuss at the time. Men in rock music were often hypermasculine, and Cobain’s advocacy for social justice came at a time when the culture wars were escalating in American politics, and the AIDS crisis and its attached stigma were at its height. These polarizing and unconventional messages of support for social justice causes came in many different forms. In the compilation album Incesticide, released in December 1992, the liner notes reflect Cobain’s public commitment to social justice: “If any of you in any way hate homosexuals, people of different color, or women, please do this one favor for us – leave us… alone! Don’t come to our shows and don’t buy our records” (Nirvana). Their next album, In Utero, would echo similar sentiments in its liner notes, “If you’re a sexist, racist, homophobe… I don’t care if you like me, I hate you” (Nirvana). These bold statements indicate Cobain and his bandmates’ championing of social justice and support of an inclusive grunge music community. Cobain’s contemptuous approach to denouncing all forms of hate is an important part of his legacy, yet remains generally underestimated. These initiatives show how his outspoken and forward-thinking attitude helped to promote inclusivity while also shifting popular rock culture.

A 1994 interview with Cobain provides a deeper look into the mind of the musical genius in the months leading up to his death, providing insight into what Nirvana may (or may not) have looked like if they had lasted longer. This archived dialogue uncovers a perspective of Cobain as a person and artist, rather than a caricature by the media. When asked about the future of Nirvana’s artistic direction and sound, Cobain responds, “It’s impossible for me to look into the future and say I’m going to be able to play Nirvana songs in 10 years […] we’re almost exhausted. We’ve gone to the point where things are becoming repetitious” (Fricke). He stressed that he did not see the band going much further because he did not want them to repeat the same sound and aesthetic. Cobain cited Eric Clapton as someone he respected but did not want to become because he believed rehashing old music would not serve to benefit any members of the band. Although Cobain’s untimely death a few months later cut Nirvana’s career short, this interview serves as a reflection of how Cobain saw himself as an artist. Always ahead of his time, he recognized that grunge would become passé and that his music would need to grow with an audience rather than be boxed into an era-defining subgenre. The responses Cobain gave in the 1994 interview demonstrate the level of personal devotion he felt to his music and fans. He always put the art above the celebrity (Fricke).

Media coverage can influence and largely determine public sentiment and action. Explaining how detailed suicide coverage can actually increase suicide rates, an article in Time Magazine remarks how journalistic publications that included specific information about how a suicide was carried out as well as news stories that framed suicide as “inevitable” were “all correlated with suicide contagion [rapid increase in suicides]” (Ducharme). Improperly portraying the stories of celebrity suicides can lead to negative repercussions such as suicide contagion or tainting a legacy. Perhaps without the media’s invasive coverage of Cobain’s death, his legacy as an artist may not have been obscured. Media outlets, and we as individuals, must be more careful in discussing these events respectfully, avoiding problematic conduct that can lead to misconceptions, falsehoods, and even more deaths by suicide. In 2019, we must not continue to repeat these damaging behaviors behind the disastrous coverage of Cobain’s death in 1994.

In the wake of the loss of senior Sydney Monfries, the Fordham community has experienced firsthand how mass media outlets can distastefully portray a tragic event. One student editorial in The Fordham Ram strongly condemns major media outlets’ “romanticization [sic] of the ‘forbidden’ campus clock tower from which Sydney fell” and claims, “the sensationalizing of the incident through its vivid description [was] as disrespectful as [it was] abhorrent” (Editorial Staff, The Fordham Ram). This unfortunate overdramatization of the tragedy in the Fordham community parallels how the media inappropriately covered Cobain’s death twenty-five years ago. Contemplating how to move forward from the Sydney Monfries tragedy, despite improper journalistic coverage, the editorial staff of The Fordham Ram continued, “The best way we at The Ram can show our respect to Sydney, her family and all those affected during this time is by reporting on her death with integrity” (Editorial Staff, The Fordham Ram). Respectful reporting on tragedies is integral to protecting the legacy of individuals.

In revisiting Cobain’s legacy, we must learn that one ill-fated event should never overpower an entire lifetime of accomplishments. Although the fixation is sometimes on his tragic death, Cobain should be remembered for his avant-garde artistic style and for inspiring a generation. Focusing too intently on the personal turmoil in his life deprives us of a full, unbiased understanding of Cobain’s cultural impact. The extent of his musical brilliance and cultural significance is rare. It is vital to remember him for these achievements, not only out of respect for his talent, but for an accurate preservation of the pop culture history that defined his generation and will continue to inspire others. Kurt Cobain has been gone for twenty-five years now, but the legacy of his life and talent is ever expanding.

Footnotes

[1] In this context, the term “anti-rock” serves to accentuate how Kurt Cobain strayed from the traditional rock star archetype and redefined rock music for a new generation. It does not imply that he was against or anti- rock music.

Works Cited

Aubrey, Elizabeth. “Hear Kurt Cobain in a Never Before Heard ‘Lost’ Interview with Nirvana from 1989.” NME, 26 Oct. 2018, www.nme.com/news/music/listen-kurt-cobain-never-heard-lost-interview-nirvana-1989-2393838.

Blink-182. “Adam’s Song.” Enema of the State, MCA Records (1999).

Ducharme, Jamie. “How Journalists and the Media Should Cover Suicides.” Time, 30 July 2018, time.com/5351106/media-suicide-coverage/.

Editorial Staff, The Fordham Ram. “Respecting the Life and Memory of Sydney Monfries.” The Fordham Ram, fordham.ram.com/68577/opinion/editorial/respecting-the-life-and-memory-of-sydney-monfries/.

Fricke, David. “Kurt Cobain, The Rolling Stone Interview: Success Doesn’t Suck.” Rolling Stone, 30 Nov. 2018, www.rollingstone.com/music/music-news/kurt-cobain-the-rolling-stone-interview-success-doesnt-suck-97194/.

Goldberg, Danny. Serving the Servant: Remembering Kurt Cobain. New York: HarperCollins, 2019.

Hall, James. “Nevermind at 25: How Nirvana’s 1991 Album Changed the Cultural Landscape.” The Telegraph, 24 Sept. 2016, www.telegraph.co.uk/music/what-to-listen-to/nevermind-at-25-how-nirvanas-1991-album-changed-the-cultural-lan/.

Hamburger, Aaron. “Yes, Kurt Cobain Was a Grunge Icon. He Was Also a Gay Rights Hero.” The Washington Post, 2 Apr. 2019, www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/yes-kurt-cobain-was-a-grunge-icon-he-was-also-a-gay-rights-hero/2019/04/01/00a62e24-50a3-11e9-8d28-f5149e5a2fda_story.html?utm_term=.ab1a248683e8.

Jay-Z, Justin Timberlake. “Holy Grail,” Magna Carta Holy Grail, Roc Nation (2013).

Kurt and Courtney. Nick Broomfield, Capital Films, 1998. Netflix.

Martoccio, Angie. “Nirvana Manager Danny Goldberg on What Everyone Gets Wrong About Kurt Cobain.” Rolling Stone, 30 Mar. 2019, www.rollingstone.com/music/music-features/danny-goldberg-interview-nirvana-kurt-cobain-serving-the-servant-814204/.

Nirvana. Nevermind, DCG Records, 1991.

Payne, Chris. “Kurt Cobain’s Suicide Note Has Become a T-Shirt.” Billboard, 13 Jan. 2015, www.billboard.com/articles/new/6436629 /kurt-cobain-suicide-note-t-shirt-nirvana-ebaby-etsy.

“Romeo Beckham Wears Nirvana Smiley Face Tee.” Pinterest, i.pinimg.com/originals/3a/2f/9c/3a2f9c08db9e6a6996b00d8a015dd1c7.jpg

Rubin, Nick. “Cobain, Kurt Donald (20 February 1967-05 April 1994).” American National Biography. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015. http://www.anb.org/view/10.1093/anb/9780198606697.001.0001/anb-9780198606697-e-1803895.

Soaked in Bleach. Benjamin Statler, Daredevil Films, 2015.