Equal Means Equal: Only Under an Equal Rights Amendment

BY Dana SkieraThe documentary Equal Means Equal (2016) examines gender inequality in the United States Legal System. The film focuses on several intertwined issues faced by women today: wage discrimination, domestic violence, and female incarceration. But what unites all of these issues throughout the film is their connection to the law’s failure to protect women and promote equal rights. Although the film includes statistics, facts, and first-hand accounts, director Kamala Lopez transforms her documentary into more than just a repetition of facts through her uses of rhetoric. While some critics, such as Julia Felsenthal, have critiqued the film for its overt chaos, I argue that this disarray has a compelling effect on its audience. That is, the chaos makes the viewer experience the same distraught women in America feel after learning they are not outright protected by a valid Equal Rights Amendment. In doing so, Equal Means Equal becomes a platform for change, leaving its viewers with the question: “Why aren’t woman explicitly protected under an Equal Rights Amendment?”

Very few Americans realize that male and female citizens do not have equal rights under federal law, meaning that women are not explicitly protected under the Constitution. Throughout the documentary, Lopez digs into this injustice of deficient protection for women under the law. For example, the film expands on this lack of definitive laws, showing how easy it is to dismiss women’s right, even in such high places as the judicial system. Evidence of women’s rights getting declined is given in the example of the Supreme Court case of Ledbetter vs. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co. Lily Ledbetter, the plaintiff of the case, was consistently given low rankings in annual performance and salary reviews, and low raises compared to her male counterparts during her 19-year career at Goodyear Tire & Rubber Company, the defendant of the case. The main employment discrimination law for this case was Title VII, a provision that requires discrimination complaints to be made within 180 days of the discriminatory act. What this means is that a person essentially only has less than six months to file the case from the day they were hired. This clause caused the Supreme Court to rule that though Ledbetter was getting lower pay during those 180 days, it could not justify ruling against Goodyear’s actions over the course of her whole career. Finding no evidence of discrimination within that 180-day period, the court dismissed Ledbetter’s complaint. As Eleanor Smeal, Co-Founder & President of Feminist Majority, explains in the documentary, the court essentially gutted the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment of 1964 (Title VII). According to Smeal, they were able to strip Title VII by stating the discrimination complaint must be filed from the day a person is hired, meaning “you really only had 180 days to file the case from the day you were hired.” This interview with a prominent feminist engages the audiences’ ethos by convincing them of the film’s credibility. The employment discrimination Supreme Court case of Ledbetter vs. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co. is just one example of many in this film that showcase how easy it is for courts to dismiss cases of gender discrimination due to lack of explicit laws protecting women’s rights under the Constitution.

On top of insufficient gender discrimination laws, Equal Means Equal also exposes a deep gender bias that plagues the judicial system. Many statistics and personal examples appeal to the viewers’ logos by including heady facts and data which support the film’s argument via logic and reason. The excess of gender bias in the American Court System can be specifically exemplified by differences between Marissa Alexander’s and George Zimmerman’s cases. In the documentary, this harsh reality of maltreatment is explored by Heidi Rummel, co-founder of the Post-Conviction Justice Project and Professor at the USC Gould School of Law. Marissa Alexander, a Florida mom, fired a warning shot into the wall of her garage to hold off her husband who had previously been charged with abusing her. She was prosecuted by the same office that handled George Zimmerman’s case; she received 20 years and did not even shoot her husband, while George Zimmerman, who never denied shooting dead unarmed Trayvon Martin, wasn’t arrested or even charged. Zimmerman wasn’t put into the criminal justice system until there was a social uproar over the shooting. The documentary provides shocking statistics, such as the fact that “up to 90% of women in jail for killing men had been battered by those men,” and that “75-80% of women who kill in self-defense end up serving long term sentences.” In addition to facts and statistics, Lopez conducts an interview with Chrystal Wheeler, a woman who served 22 years in Chowchilla Women’s Prison for killing her husband in self-defense after years of abuse from him. Lopez expertly appeals to viewers’ pathos through Chrystal’s first-hand, personal account of her injustice. This discrimination flourishes due to the absence of a valid Equal Rights Amendment in the United States, which would make the principals of equal rights concrete under law and under the Constitution.

Although the need for a valid Equal Rights Amendment is clearly expressed in Lopez’s documentary Equal Means Equal, film critic Julia Felsenthal, a writer for Vogue, has asserted that “Equal Means Equal can be a slog; then again, so is life as a woman in America” (Felsenthal). According to Felsenthal, the “horrifying darkness” of the stories and “the frenetic nosiness of Lopez’s presentation” makes for an “overwhelming viewing experience” (Felsenthal). Anyone who has seen the film will notice how the documentary presents numbers and facts at a breakneck speed, superimposing so much information that it is impossible to process one fact before the next comes on screen. She argues that the stressed-out instrumental music and the constant rhetorical questions being asked into the camera only add to a mounting tension. For Felsenthal, these displays distract from the main point of the documentary, the need for a valid Equal Rights Amendment.

Not only do Felsenthal and other critics call attention to the film’s chaotic exhibition, but they also explain that this chaos embodies what life is like as a woman in America. Helen T. Verongos, of The New York Times, comments how the documentary is “broader than it is deep,” while Tomris Laffly, of the Film Journal International, states that Lopez applies “a ‘table of contents’-type treatment to our shared frustration as females,” and Frank Scheck, of The Hollywood Reporter, remarks “the cinematic clumsiness is a shame because Equal Means Equal makes many powerful points along its… way” (Verongos; Laffly, Scheck). Most critics agree with Felsenthal that Lopez’s documentary is disordered or broad in its showcase and that it generates a collective frustration towards the American legal system’s lack of true equality for women. But they also note that the disarray created by these displays simultaneously create an awareness of the need for change. As Felsenthal comments, the displays also symbolize an equally disorganized and unsettled system in America. The chaos of the documentary “actually drives Lopez’s point home: wouldn’t it be nice if there were just one federal law to simplify matters, to establish equality once and for all?” (Felsenthal).

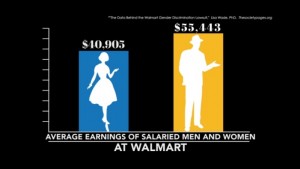

Extrapolating from Felsenthal’s claim, I believe that the inherent pandemonium of the documentary does not just symbolize life as an American woman, but also makes the viewer experience the same distraught a woman in America feels after learning she is not explicitly protected by a valid Equal Rights Amendment. All the interviews and facts that burst across the screen help create this agitation, which Felsenthal describes as “racing through a poorly organized PowerPoint presentation” (Felsenthal). These visuals, such as the examples below, alongside interviews and first-hand accounts of injustice create a sense of urgency regarding gender discrimination throughout the documentary. A specific instance of this urgency being created can be seen in the documentary’s discussion of Walmart, known by nearly every American and employer of 1.3 million people. The documentary speeds from fact to fact about discrimination at Walmart, going from a map with all of Walmart’s sales to a single mother talking about her pay degrade from Lowe’s to Walmart and then to Betty Dukes remarking on “the pattern of discrimination at Walmart” (Equal Means Equal). The accumulation of all these displays creates an immense sense of urgency regarding the systematic discrimination of women, adding to viewers’ experience of distraught that a woman in America feels.

What Felsenthal fails to grasp is that the visuals Lopez utilizes to showcase women’s inequality also creates a dialogue rich in the rhetorical appeals of ethos (ethics), pathos (emotion), and logos (logic). Ethos is achieved through an abundance of startling facts and credible sources, such as legal documents and statistical data. Pathos is produced through the interviews Lopez conducts with a plethora of American woman who have faced injustice in many different areas of life. Logos is developed by a build-up of both facts, credible sources, and first-hand accounts of injustice, which unite to strike in the viewer an appeal to the logical side of giving woman valid equal rights. These three rhetorical appeals come together to showcase the main point of an overall failure of the law to protect women and promote equal rights, as showcased by the documentary. Most of all, the rhetorical appeals of ethos, pathos, and logos conclusively amalgamate throughout the documentary to leave all viewers, even those who have not experienced gender discrimination, wondering why there is no sound Equal Rights Amendment that unequivocally protects women.

Kamala Lopez’s Equal Means Equal shines a light on the fact that gender inequality in the United States is not over. It is not something that was radicalized during the 1960’s and fixed in one decade, “given the common yet false belief in society that sexism is ancient history” (Laffly). Sex discrimination is a long, on-going battle that women feel today. As Helen T. Verongos writes in a New York Times review of the film, “Equal Means Equal still drills down into enough specific issues to shock us afresh” (Verongos). The film emphasizes the point that women still need to fight for equal rights. The cases of the gender wage gap and unjust female incarceration show how women should not be complacent with their status in American society and should keep fighting for the rights many women might not even know they don’t possess. Most of all, we learn that women are still unprotected under the Constitution, the principal document where all United States laws come from. Equal Means Equal is a forerunner in making people aware of the need for change, leaving its audience wondering why women do not have an explicit Equal Rights Amendment. Many people say that America is the greatest place in the world, but how can any place be the “greatest” if it is putting down more than half of its population? No claim to greatness can be rewarded until all are protected under the legal system of the United States and a valid form of equal rights is promoted. It is time for an unequivocal Equal Rights Amendment in the United States of America, a legal policy that might one day legitimately represent the true meaning of freedom for every person in the United States.

Works Cited

Equal Means Equal. Dir. Kamala Lopez. Perf. Kamala Lopez and Patricia Arquette. Heroica Films, 2016.

Felsenthal, Julia. “Equal Means Equal Is a Chaotically Hard-Hitting Look at Gender Discrimination in America.” Vogue, 25 May 2017. www.vogue.com/article/equal-means-equal-documentary-review.

Laffly, Tomris. “Film Review: Equal Means Equal.” Film Journal International, 24 Aug. 2016. www.filmjournal.com/reviews/film-review-equal.

“Ledbetter v. Goodyear Tire and Rubber Company.” Oyez, 13 Nov. 2017, www.oyez.org/cases/2006/05-1074.

Scheck, Frank. “’Equal Means Equal‘: Film Review.” The Hollywood Reporter, 31 Aug. 2016. www.hollywoodreporter.com/review/equal-means-equal-film-review-924723.

Verongos, Helen T. “Review: ‘Equal Means Equal‘ Asks How Far Women Have Really Come.” The New York Times, 1 Sept. 2016. www.nytimes.com/2016/09/02/movies/equal-means-equal-review.html.